Harlem Late Night jazz Presents:

Bebop: 1940

HARLEM LATE NIGHT JAZZ Presents:

Bebop: 1940

The Jazz History Tree

Many consider the birth of bebop in the 1940s the beginning of “modern” jazz. Bebop developed as the younger generation of jazz musicians expanded the creative possibilities of jazz beyond the dance-oriented swing style.1 It was aided in part by the cabaret laws that began to emerge in the ’40s, designed in part to curb interracial dancing. This style grew directly out of the small swing groups but placed a much higher emphasis on technique and on more complex harmonies rather than on singable melodies.

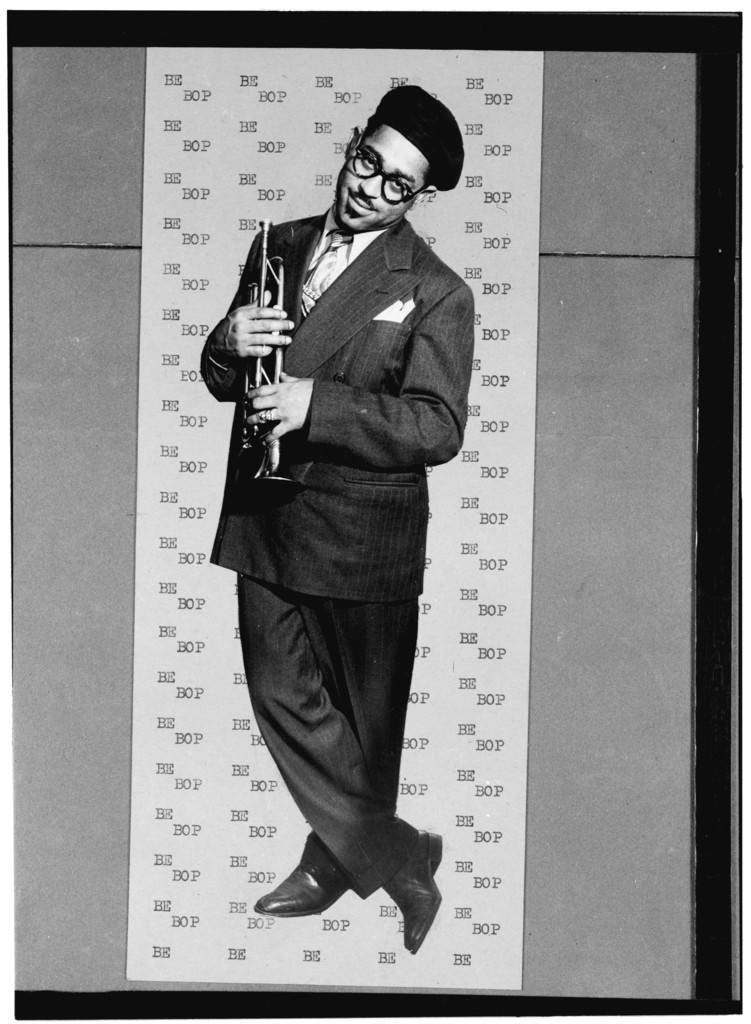

Alto saxophonist Charlie “Bird” Parker was the father of this movement, and trumpet player (and big band leader) John Burks “Dizzy” (or “Diz”) Gillespie was his primary accomplice. When Parker started to hang out at Minton’s Uptown Playhouse in Harlem and jam with Gillespie, things started to happen. They jammed with the house pianist, Thelonious Monk, and bebop was born. Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie formed a small group that arguably played the best bebop ever heard.2

This new “musician’s music” was not as danceable and demanded close listening. It also expanded the musician’s freedom. With a focus on improvisation, bebop allowed for an explosion of innovation. Inspired by the more harmonically and rhythmically experimental players from the swing era—such as Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Art Tatum, and Roy Eldridge—bebop musicians expanded the palette of musical devices. As bebop was not intended for dancing, it enabled the musicians to play at faster tempos. The advent of bebop also marked an expansion of the roles of the rhythm section.

While it can be argued that bebop has given jazz its greatest freedom of expression, bebop was unacceptable not only to the general public but also to many musicians when it emerged. The lack of bebop’s “danceability” may have been at the center of this schism. The resulting breaches were deep—first between the new and old generations of jazz musicians, and secondly between these musicians and their public. For all the criticism many established jazz musicians leveled at bebop’s inception (including the great Louis Armstrong, who condemned the new music as noisy and “un-swinging”), bebop became the biggest single influence on all popular music in the last half century.3

Notable musicians of the bebop movement include Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Mary Lou Williams, Sonny Stitt, Thelonious Monk, Dexter Gordon, Lucky Thompson, “Fats” Navarro, Kenny Dorham, Sarah Vaughn, Ella Fitzgerald, Roy Haynes, Milt Jackson, Oscar Pettiford, Charles Mingus, and Max Roach, to name a few.

Footnotes:

1 Eric Lott, “Double V, Double-Time: Bebop’s Politics of Style,”Callaloo 36 (Summer 1988).

2 Cameron K., “Brief History of Bebop,” Jazz Quotations, http://www.jazzquotations.com/2010/05/brief-history-of-bebop.html. 3 Cameron K., “Brief History of Bebop.”