Harlem Late Night jazz Presents:

NEGRO/AFRICAN AMERICAN SPIRITUALS

HARLEM LATE NIGHT JAZZ Presents:

NEGRO/AFRICAN AMERICAN SPIRITUALS

The Jazz History Tree

African American (Negro) spirituals emerged from a mix of the brutal institution of slavery, Christian influences, and African culture. The songs expressed a yearning for a better life, claimed identification with the children of Israel, named the slave owner’s deceit and hypocrisy, underscored the need for a closer walk with God, identified the reality of Satan, and emphasized the slave’s hope for freedom and the future. Love, grace, mercy, judgment, death, and eternal life are among the themes enfolded in these songs.1

The form has its roots in the informal gatherings of African slaves in “praise houses” and outdoor meetings called “brush arbor meetings,” “bush meetings,” or “camp meetings” in the eighteenth century. At the meetings, participants would sing, chant, dance, and sometimes enter ecstatic trances. Spirituals also stem from the ring shout, a circular dance, to the chanting and hand clapping that was common among early plantation slaves.

By the mid to late 1700s, free African Americans began forming religious groups apart from white congregations, organized by people educated by Methodists, Baptists, or the Society of Friends (Quakers), especially in the North. In some cases, these efforts culminated in the development of fully independent African American churches.

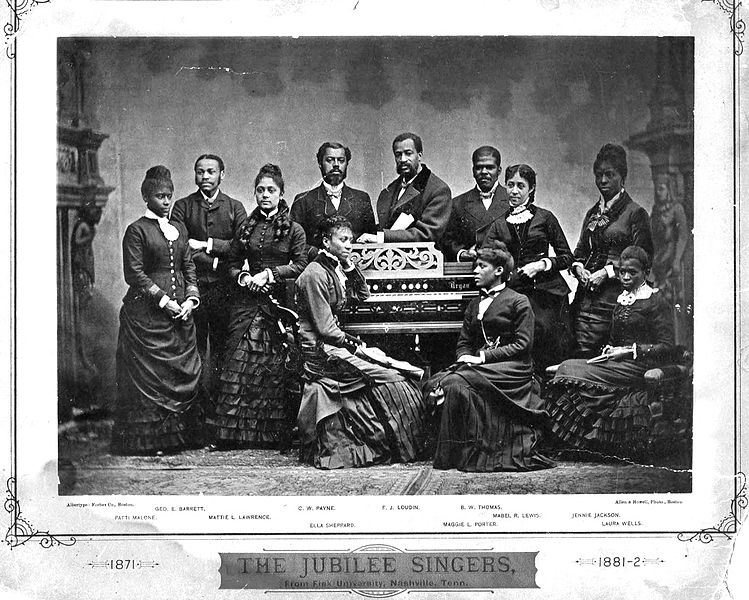

In the 1870s, the creation of the Jubilee Singers—a chorus consisting of former slaves from Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee—sparked an international interest in the musical form. The group’s extensive touring schedule in the United States and Europe included concert performances of spirituals that were very well received by audiences. While some African Americans at the time associated the spiritual tradition with slavery and were not enthusiastic about continuing it, the Fisk University singers’ performances persuaded many that it should be continued.2

The key elements of Negro spirituals include call and response, which made its way to subsequent genres of music such as the blues, jazz, and gospel. In some ways, Negro spirituals were a form of resistance. Slaves did not want to conform to European ways and wanted to keep the African elements of their music as a reminder of their identity. We say that the Negro spiritual was a form of resistance because the history of Negro spirituals is closely related to African American history at large. Negro spirituals and their social implications were tied to the abolition of slavery in 1865, the black renaissance, and the first Martin Luther King Jr. (MLK) Day.3Indeed, Negro spirituals are still fulfilling their spiritual purpose. In the words of writer Pamela Crosby, “African American spirituals still heal.”4

Footnotes:

1 Pamela Crosby, “Part of history, African-American spirituals still heal,” from Interpreter, Jan-Feb 2014, UMC,org, 2019, http://ee.umc.org/resources/part-of-history-african-american-spirituals-still-heal.

2 Library of Congress, “African American Spirituals,” loc.gov, https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200197495/.

3 Kalia Simms and Betanya, Mahary The History of Negro Spirituals and Folk Music. https://blackmusicscholar.com/negro-spirituals-and-folk-music-kalia-simms-and-betanya-mahary/.

4 Pamela Crosby, “Part of history, African-American spirituals still heal,” from Interpreter, Jan-Feb 2014, UMC,org, 2019, http://ee.umc.org/resources/part-of-history-african-american-spirituals-still-heal.